How could America lose the Vietnam War?

Even now, 50 years after the last American helicopters left Saigon, the answer is elusive. Despite pouring immense resources into Vietnam — including nearly 3 million military personnel, and suffering 58,000 dead — the world’s most powerful nation was unable to defeat an enemy that seemed hopelessly inferior in military power.

Accusations still fly at a long list of alleged culprits: “pinkos,” war hawks, hippies, the China Lobby, Jane Fonda, John Wayne, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. But can a tabletop wargame — that began life as a college student’s project — offer insight?

“Vietnam 1965-1975” was conceived in the early 1980s when Nick Karp, a Princeton University student, needed to complete his senior thesis. So Karp designed a board game that was published as a hobby game in 1984, and is still available today from GMT Games.

A game of firepower

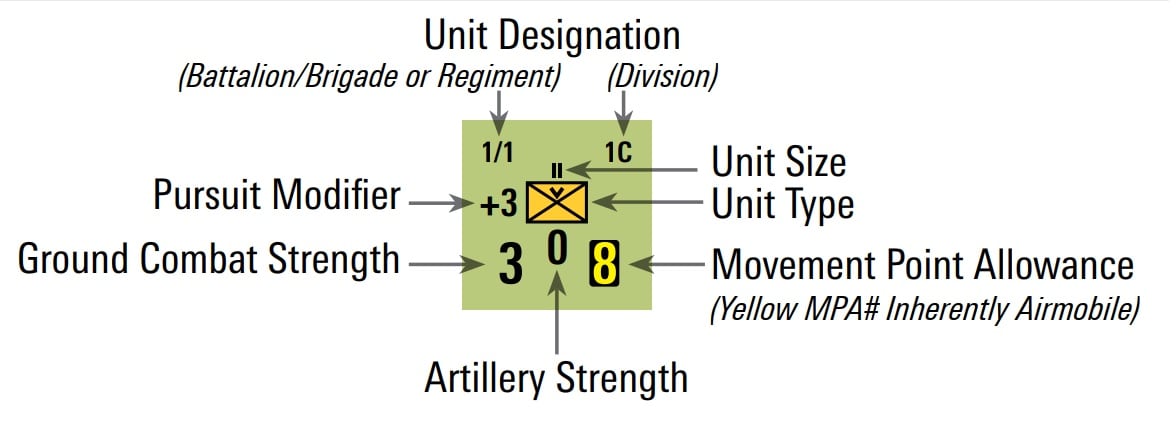

As befitting such a massive struggle, “Vietnam 1965-1975” is a massive game. The GMT edition includes a 44-page manual, a 5-foot-by-3-foot map and 1,328 small cardboard pieces that depict combat battalions and regiments, as well as various informational markers.

The order of battle alone illustrates the polyglot nature of the conflict. On the Allied side are more than a dozen U.S. Army and Marine divisions and brigades that fought in Vietnam, or could have been sent, plus numerous independent artillery and mechanized battalions. Alongside them is the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, plus contingents of Australian, South Korean, Thai and Philippines troops. Opposing this coalition is the National Liberation Front and North Vietnamese Army divisions — mostly infantry, backed by some artillery and mechanized units — and a plethora of Viet Cong battalions.

The game is played over an L-shaped map stretching from the hills of the Demilitarized Zone in the north to the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta in the south.

Each turn — equivalent to one season of real time — the Allied and NLF players conduct various “operations” including search and destroy, clear and secure, hold and patrol, bombardment and strategic movement. To win the 1965-1975 campaign scenario, the Communists either have to capture Saigon, or control the bulk of the South Vietnamese population. The Allies need only surpass their real-life counterparts: If South Vietnam survives until early 1975, they win.

At first glance, the game looks like a slam dunk for the U.S. The Allies have copious amounts of tactical airpower, artillery and naval gunfire. Helicopters can whisk U.S. and ARVN troops over rough terrain, while tank and armored cavalry units prowl the roads. Strategic bombing can disrupt the North Vietnamese war effort and interdict troops and supplies moving down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Combat is resolved by rolling dice. The game’s combat system favors whoever can employ the most firepower in a battle, and that is rarely the Communists. It’s not that the Allies won’t take casualties. But the NVA and VC will suffer many more.

Death by a thousand cuts

So why doesn’t America crush the Communists by 1968, and LBJ win reelection instead of leaving the White House? Because like the proverbial death by a thousand cuts, a lot of little things undermine what seems like overwhelming power.

For starters, the terrain is mostly unfavorable for Western-style mechanized armies. Jungles and hills impede movement and provide defensive bonuses during combat. Allied firepower is immensely lethal but restricted unless the battlefield is declared a free fire zone, which undercuts support for the Saigon government.

Much of the Allied frustration comes from the difficulty of counterinsurgency. The map divides South Vietnam into 35 regions, each with a certain level of population. Dice are rolled each turn for each region to determine what percentage is pro-Saigon or pro-Communist, which in turn determines how much manpower is available to recruit ARVN or Viet Cong troops. The more VC/NVA units in a region, the greater the population that backs the Communists. Yet the presence of Allied troops in a region doesn’t generate support for Saigon, perhaps because ARVN troops had a reputation for robbing the peasants.

To win the support of the populace, the obvious solution is to destroy the Viet Cong in the countryside. But that’s easier said than done. Though weak in combat power, Viet Cong guerrillas have a special ability to evade Allied search-and-destroy operations. Cornering even a weak VC battalion can require three or four U.S. battalions — the ARVN aren’t mobile enough — and there are too few U.S. troops to hunt down all the VC.

Every turn, Communist units are wiped out, only to be replaced by new ones. NVA regiments infiltrate the South via the Ho Chi Minh trail through Cambodia and Laos. Fresh VC units sprout in every region, using local pro-Communist manpower as well as arms sent down from the North.

A war of whac-a-mole

The game captures the dilemma that confounded the Pentagon. To stop the Viet Cong from controlling the countryside means Allied troops have to fan out to surround the guerrillas. But splitting up to hunt VC leaves the Allies vulnerable to being jumped by North Vietnamese regulars that can be lethal against the ARVN or an isolated American unit.

“The game’s operational core shows how U.S. commanders whose forces possessed far greater firepower and mobility than their opponents could rarely bring those seemingly decisive advantages to bear against Communist units that generally fought only when it suited them,” Kevin Boylan, a Vietnam War historian and wargame designer, told Defense News. “The game illustrates how this fundamental asymmetry at the operational level caused the war to drag on so long that a critical mass of the American people lost patience with it at the strategic level.”

“Vietnam 1965-1975” melds both the operational and strategic aspects of the war.

For example, South Vietnam’s unstable political system has battlefield consequences. The game assigns each ARVN corps and division a randomly chosen commander with varying levels of competence and loyalty to the regime. Each turn, dice are rolled for loyalty, and a bad roll means that some ARVN formations will stay immobile in their bases that turn. If enough commanders are disloyal, there will be a coup that can shake up the ARVN command structure.

A credit card war

But if there is one mechanism in the game that best explains why America ultimately failed in Vietnam, it’s the “morale” and “commitment” system. Essentially, the game depicts the U.S. war effort as a sort of credit card where America starts with a huge credit limit.

The U.S. begins the game in the summer of 1965 with a “morale level” of 520 and a “commitment level” of 25 (reflecting American aircraft and advisers already in South Vietnam). Want to send the 1st Cavalry Division or the 3rd Marine Division? That will cost you around 10 “commitment points” apiece. A battalion of 155mm artillery or a Navy cruiser? They’re one point each.

At first, the Allied player is like a college kid with a new Visa card. There are practically limitless resources on the shelf. Aircraft, helicopters, supplies to equip ARVN divisions, South Korean troops, replacements for American casualties. Everything is available, but everything costs commitment points.

Meanwhile, there are a litany of factors that decrease morale, including sending fresh troops to Vietnam, invading Laos or Cambodia, losing provincial capitals, bombing North Vietnam or if the Communists declare a special offensive. Morale also goes down each turn as commitment grows over time, reflecting the inevitable fatigue of a long war. Unless the Allies wipe out a lot of Viet Cong in a turn, morale will only go down, not up.

Eventually, the bill becomes due. The rule in “Vietnam 1965-1975” is simple and unequivocal: U.S. commitment cannot exceed morale. If it does, then America must reduce its forces in Vietnam to balance the books.

And so the long U.S. withdrawal begins. An infantry brigade here, a tank or artillery battalion there. Once the tipping point is reached, each turn the U.S. presence in Southeast Asia shrinks a little more. And a little more. Perhaps the pullout begins in 1969, as Nixon chose to do as part of his “Vietnamization” of the war. Or in 1968, or 1970. But sooner or later, South Vietnam will have to fight on its own in a desperate battle to stave off Communist invasion from within and without.

Can history be changed?

That American society became too weary and fractured to continue fighting in Vietnam is hardly a revelation. But while a book or a documentary can describe history, the fascination of a historical wargame is the chance to experiment with it. Both sides in “Vietnam 1965-1975” can pursue a variety of strategies.

For example, the Allies can choose to accelerate the buildup in Southeast Asia by dispatching troops more quickly than LBJ did, taking an extra hit to morale in order to hit the Communists sooner. Or, Washington can send fewer troops in a bid to preserve public support and delay the U.S. withdrawal. American troops can fight more aggressively in the early war, suffering additional casualties and morale loss in hopes of suppressing the Communists before they take root in the countryside. Or, they can adopt a more passive strategy that minimizes U.S. losses but leave the VC unmolested as they take over the countryside.

The Communists have options, too. Spread VC units across Vietnam to control the population, or concentrate and risk heavier losses to capture provincial capitals? Avoid contact with U.S. troops while going after weaker ARVN units, or conduct hit-and-run raids on U.S. units to inflict casualties and undermine American morale? Either way, the Communists will patiently wait for the Americans to leave before going for final victory.

Can America win the game? It seems unlikely. Once U.S. troops and airpower are gone, the ARVN seems too brittle to defeat the NVA and VC. Indeed, Karp himself admits that his goal in designing the game wasn’t to create a fair contest between two players, but rather to model a crucial period in American history. The game was aimed at “reproducing a mood and understanding of competing priorities, not scrupulously documenting inevitably contingent details,” he told Defense News.

“I wasn’t trying to make a deep statement about favorites to win, nor the futility of the war either,” he added. “The victory conditions are far off, the road to achieve them vague and wandering.” In fact, Karp said he would “no way be offended” if players modified the game “either to improve their play experience or to better conform to their understanding of history.”

Every war is unique, and there is a danger in searching for too many lessons of the Vietnam War. But this tabletop game illuminates a problem that resonates today. U.S. troops fought for years in Afghanistan and Iraq before the American public and its leaders grew weary of the global war on terror. How long — and at what cost — will the American public endure fighting in distant lands, be it in Eastern Europe or Taiwan?

“The United States had the raw military and economic power to prevail if it had waged total war in Indochina,” Boylan said. “But, as the game makes clear, the American people had no stomach for that. And the war was effectively unwinnable at the level of commitment that they were willing to sustain.”

Michael Peck is a correspondent for Defense News and a columnist for the Center for European Policy Analysis. He holds an M.A. in political science from Rutgers University. Find him on X at @Mipeck1. His email is mikedefense1@gmail.com.